The book, It’s High Time: Women Religious Speak Up on Gender Justice in the Indian Church, found sacramental blackmail, clergy sexual abuse, clericalism and property disputes as some major challenges facing Catholic women religious in the country.

“We train nuns to understand different forms of abuse, not only sexual but verbal and other forms.”

Bhopal, India — February 15, 2024 by Saji Thomas, View Author Profile, Share on FacebookShare on TwitterEmail to a friendPrint

Sr. Leena Padam is hopeful that Catholic nuns in India now have a platform for a “proper hearing and legitimate settlement” of their grievances.

“Until now, women religious in India did not know where to air their grievances, but today we have a platform to share our problems without fear of retribution,” Padam, a member of the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth, told Global Sisters Report.

Padam was among around 100 nuns who attended a special training on the Grievance Redressal Cell (GRC), an initiative of the Conference of Religious Women India, in the eastern Indian city of Kolkata.

The conference launched the cell on Dec. 10, 2023, through a virtual program for more than 100,000 Catholic religious women in India. It is a place to hear the nuns’ grievances, acknowledge them and find a solution through dialogue.

Sr. Leena Padam, a member of the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth (Courtesy of Leena Padam)

“Definitely, it is a ray of hope for nuns, especially the young ones,” asserted Padam after the Jan. 19-21 training, the second one to educate nuns about the objective of the cell. Nuns from northern, eastern and northeastern Indian states attended it.

The first training was held Dec. 27-29 in the southern Indian city of Bengaluru for nuns from southern states.

Padam, a social activist based in Ranchi, the capital of the eastern Indian state of Jharkhand, noted, “Generally when a nun complains against a priest or an ecclesiastical authority within the church, she is not trusted. Even her superiors tend to believe what the priest or the bishop says.”

Nuns can now approach the grievance redressal, the proper channel, without hesitation. “It is assured that she will be heard, and a solution to her problems will be found if it is possible within the church setup,” she said.

Apostolic Carmel Sr. Maria Nirmalini, head of India’s more than 130,000 Catholic men and women religious, describes the cell as relevant and timely. “Despite all the systems and care we have in place, some unfortunate circumstances can lead to a feeling of extreme isolation even when one is part of a community and family,” she told GSR.

She says the cell is “a way of acknowledging this need and trying our best to provide relief where possible within our community.”

An interactive session takes place during the Jan. 19-21 training on the Grievance Redressal Cell launched by the Conference of Religious Women India, at the Jesuits’ Dhyan Ashram Retreat Centre in the eastern Indian city of Kolkata. (Courtesy of Elsa Muttathu)

The impetus to launch the cell was a book on gender discrimination within the church in India, published by the women’s section of the conference in 2018.

The book, It’s High Time: Women Religious Speak Up on Gender Justice in the Indian Church, found sacramental blackmail, clergy sexual abuse, clericalism and property disputes as some major challenges facing Catholic women religious in the country.

The 86-page book written by a three-member team led by Sr. Hazel D’Lima, former superior general of the Society of the Daughters of the Heart of Mary, also highlighted the “gender injustice” Catholic nuns suffered under the patriarchal church.

Presentation Sr. Elsa Muttathu, national secretary of the Conference of Religious India who leads the trainings, regrets that in many cases, even nuns are not aware of the kind of abuses they suffer from within the system.

“We train nuns to understand different forms of abuse, not only sexual but verbal and other forms, and tell them how to approach the cell,” Muttathu told GSR.

Participants listen during a session of the first Grievance Redressal Cell training, held Dec. 27-29, 2023, at Jesuits’ Indian Social Institute in the southern Indian city of Bengaluru. (Courtesy of Nambikai Mary)

She said they have a three-member screening committee that will first study the complaint, and if found true, it will be referred to a nine-member committee.

“The committee consists of five nuns, a religious priest or a brother. The other members are eminent female personalities who are well-versed in the functioning of Catholic religious women,” she explained.

Muttathu also said that no major superior is allowed to become a member of this committee, to maintain its neutrality and effective functioning. “In most cases, nuns approach the GRC after they failed to get justice from their congregations,” she noted.

“The committee’s jurisdiction is within the church framework and will not go for a legal fight in a civil court. However, if the matter needs legal attention, we will support the complainant taking legal recourse but will not be involved directly,” Muttathu said.

Sr. Mary Scaria, a member of the Sisters of Charity of Jesus and Mary who is a New Delhi-based Supreme Court of India lawyer, addresses participants in the Jan. 19-21 training on the Grievance Redressal Cell launched by the Conference of Religious Women India, at the Jesuits’ Dhyan Ashram Retreat Centre in the eastern Indian city of Kolkata. (Courtesy of Elsa Muttathu)

According to the draft guideline drawn by the conference, an aggrieved member can lodge a complaint to the cell either by telephone, in written form or by email. Once the complaint is lodged, it will be acknowledged within seven working days.

The acknowledgment includes a unique grievance number and the mode of tracking its progress.

The Grievance Redressal Cell, however, will not entertain an issue that is before a court or under a police probe.

The guideline promises to resolve a normal complaint within 30 days. A complex and sensitive complainant will take more time, and the cell will inform the complainant about the delay.

If a complainant fails to respond to the cell’s written response in 45 days, the matter will be considered as closed.

The cell assures to keep confidential the complainant’s identity and the details about the complaint unless required by an external agency to resolve the crisis, that too with prior consent.

The cell will conduct its proceedings like in a civil court — issue notice to the accused, seek written reply, examination of witnesses and do fact-finding, among other actions.

The cell aims to close even a serious case within 90 days to avoid delay in getting justice for the complainant.

Anita Cheria, a Catholic human rights activist, speaks during the Jan. 19-21 training on the Grievance Redressal Cell in Kolkata, India. (Courtesy of Anita Cheria)

Anita Cheria, a human rights activist based in the southern Indian state of Bengaluru, said the “whole idea of this mechanism is to transform religious life to happiness and worth.”

“Within the Catholic church, there are many systems in place, but I still have come across nuns in desperate positions pushed to extreme steps like suicide or leaving the congregation,” Cheria, a Catholic laywoman and one of the resource persons for the training, told GSR.

She said in many cases, the complainant was treated as a troublemaker in the congregation and isolated, leaving no room for addressing her issue.

“In some cases, the superiors defend the accused, making the complainant more vulnerable,” Cheria said.

Since 1997, more than 20 nuns have reportedly committed suicide in India, most of them in Kerala, a Christian stronghold in the south.

Cheria says a hearing would have helped many to avoid resorting to extreme steps. “The new initiative is a major step forward to address issues confronting nuns within the patriarchal system,” she explained.

Sr. Nambikai Mary, secretary of the conference’s Tamil Nadu and Pondicherry unit in southern India, says nuns now feel they have a place where they will be heard.

Sisters participate in a session of the first Grievance Redressal Cell training, held Dec. 27-29, 2023, at Jesuits’ Indian Social Institute in the southern Indian city of Bengaluru. (Courtesy of Nambikai Mary)

Mary, a member of the order of St. Ann of Providence who attended the training in Bengaluru, told GSR, “Nuns suffer harassment of different nature from within the church setup and outside, but most often they are unable to stand up and oppose them as they lack support from within the congregation or the church.”

She says the Grievance Redressal Cell is “not merely a consolation but a source of strength.”

Muttathu said the training is not restricted to abuses within the church but also covers important laws such as the Protection of Children from Sexual Offenses Act of 2012, a federal law to protect children from all forms of sexual abuse, and the Prevention of Sexual Harassment at Workplace Act.

The workplace law mandates that every organization define its sexual harassment policies, prevention systems, procedures and service rules for its employees, among other things, the national secretary said.

Cheria congratulates the women’s section of the conference for setting up the GRC, but “it is a big challenge to take forward in a patriarchal church set up. Since it is set up within the CRI framework, it has legitimacy, and we are hopeful that slowly, the church authorities will accept this change in India as the Vatican has zero tolerance to abuses of all forms.”

https://www.ncronline.org/news/training-grievance-redressal-infuses-hope-among-indian-women-religious

Panaji, India — July 12, 2021, Share on FacebookShare on TwitterEmail to a friendPrint

Sacramental blackmail, clergy sexual abuse, clericalism and property disputes are among challenges facing Catholic women religious in India, an international webinar was told.

The July 10 meeting organized by Voices of Faith, a Rome-based international network, discussed the findings of a Conference of Religious India survey conducted among the leaders of the women religious in the country.

Around 370 nuns, priests and laypeople from many English-speaking countries, Germany and Italy attended the two-hour program.

The survey was commissioned in 2018 by the women’s section of the Conference of Religious India, the national association of religious major superiors in the country, after media reports indicated widespread exploitation of nuns in the Catholic Church.

A four-member team conducted the study in 2019-20 and published the findings as a book in June this year.

“It is a landmark document,” Astrid Lobo Gajiwala, a laywoman theologian who coordinated the webinar, said of the book. “For the first time, we have hard data that cannot be discounted. Women religious from across India have courageously called out the exploitation they experience in the church.”

Astrid Lobo Gajiwala, a lay theologian, moderates an international webinar organized July 10 to discuss the findings of a study on Indian women religious. (Lissy Maruthanakuzhy)

The book lists these problems faced by the Indian nuns: low wages, disputes over property, harassment from priests, refusal of sacramental celebrations, and verbal abuse in person and from the pulpit.

The issues discussed in the book were earlier discounted, Gajiwala says, lest they invite “the wrath of powerful priests and bishops,” adding the concerns “are finally out in the open.”

The India conferences of both bishops and religious have not responded to the survey or its findings.

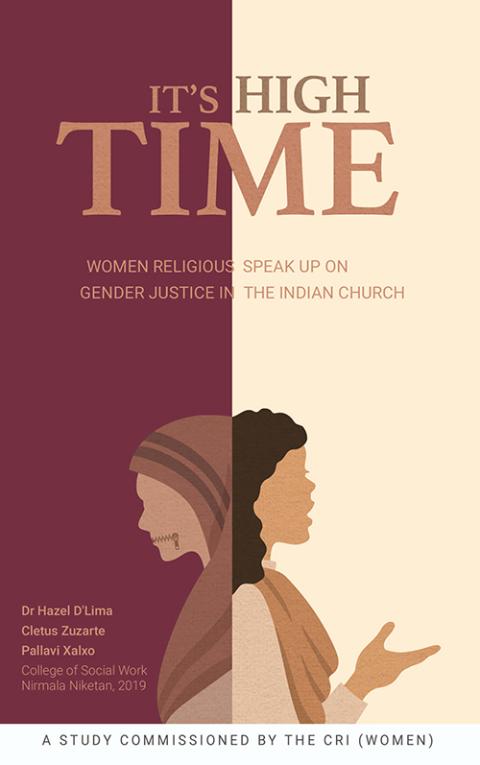

The 86-page book titled It’s High Time: Women Religious Speak Up on Gender Justice in the Indian Church, was written by a three-member team led by Sr. Hazel D’Lima, former superior general of the Society of the Daughters of the Heart of Mary.

The team contacted about 500 women major superiors and persons of influence in different women’s religious congregations in India. “Only 121 people replied. A 25% sample is good enough for an exploratory survey,” D’Lima told the webinar.

Sr. Noella de Souza of the Missionaries of Christ Jesus, a member of the survey team, said the book speaks of the economic, spiritual and sexual abuses women religious face in the Indian church.

The cover of “It’s High Time: Women Religious Speak Up on Gender Justice in the Indian Church” (Courtesy of Noella de Souza)

India has more than 103,000 members in 292 women religious congregations, according to the conference of religious directory.

De Souza said they were told that bishops were not happy about the survey. “Later, the executive commission of [the Conference of Religious India] seemed plagued by fears and withheld their consent to publish the study,” she explained.

“Towards the end we had to seek legal counsel to reassure ourselves that we could and should get it printed and, more important, disseminate the study to all the respondents and bishops in the country,” De Souza said.

The study was “almost silent” about clergy sexual abuse, she said, “because the respondents were major superiors and not the sisters in the field.”

The webinar, she said, was organized to take the book’s message further. “Being the first study of its kind, we were keen to know the issues that mattered to our sisters, and their feelings about the working relations in the mission,” she explained.

She expects the participants to take the message to their congregations, dioceses and bishops.

Br. Philip Pinto, who wrote the book’s preface, endorsed the study. “I have sat in silence as individual sisters wept through telling their stories. Enough! It’s high time. … This is now the call for action,” asserted the former superior general of the worldwide Congregation of Christian Brothers. Pinto was a panelist in the online forum.

D’Lima said women religious expect priests and bishops to understand and respect their role in the church’s mission. Instead, sisters “face a sense of rivalry and fear to dialogue. Too many demands are made on them,” said D’Lima, who once headed the women’s section of the India conference of religious.

She said the lack of understanding and respect from the priests makes the mission difficult for women religious. Priests don’t have a sense of shared planning and execution of tasks in the church’s mission, D’Lima said.

“Dialogue often leads to hostility between priests and women religious,” she added.

Sr. Hazel D’Lima of the Society of the Daughters of the Heart of Mary led the recent study on the status of women religious in India. (Courtesy of Hazel D’Lima)

The researchers spent months analyzing the data, reflecting on each response and the message it sought to convey, D’Lima said.

According to the respondents, working relationships are most important in their mission to build confidence, understanding and encouragement. They expect priests and bishops to respect and appreciate their efforts, potential, and their religious and community life.

The book says nuns who work in church institutions are among the lowest-paid employees. Those working in sacristy or preparing for liturgy get no payment. Around 47 of 174 dioceses in India paid low wages to nuns. The hierarchical response has been that nuns are “collaborators” in the church’s mission.

“Women religious are considered less than other laywomen when it comes to their service in parishes, although they are qualified and do equal work. They are offered a paltry sum for their full-time services,” De Souza said.

Land has become a “bone of contention” in the church, with some religious going to civil courts to resolve their disputes with dioceses.

Pinto said dioceses bully and intimidate women religious since they hesitate to go to court for redress of their grievances. He wants the religious, especially women, to pay greater attention to their initial contracts with dioceses.

“The church is not just the hierarchical church. We are the church. The diocese is not the only element of the church in mission. All of us are players in the field and this needs to be acknowledged and provided for,” said Pinto.

Women keep the church alive, he asserted. “If women stopped going to church, the church would die — no matter how many men line up for ordination.”

Another problem is sacramental blackmail, or a priest’s refusal of sacramental celebration to sisters. Some priests use their power arbitrarily when they refuse to celebrate Mass in the convent chapel or they take away the Blessed Sacrament from there.

Christian Br. Philip Pinto addresses an international webinar held July 10 to explain the findings of a study on the status of women religious in India. (Lissy Maruthanakuzhy)

Most survey respondents said priests refuse to say Mass when the sisters do not comply with their demands. Normal expectation is that the priest would celebrate Mass once a week in a convent. “However, there have been instances where the Eucharist was not celebrated even for months,” says the book.

“Such abusive behavior can be stopped only by refusing to tolerate it,” said Pinto. “Like Pope Francis who allowed a cardinal to stand trial for fraud in the Vatican, we must not be party to abusive behavior. That is transparency and a sign of change,” he added.

De Souza said religious congregations should train their young people to think critically and face uncomfortable and exploitative pastoral situations with courage.

She regrets that many nuns stop their spiritual and emotional growth when they join the convent. “What are we doing to our young recruits? And this comes to the question of formation.”

De Souza said the religious congregation should focus on human development while training their new members.

“We should train our young sisters in legal and human rights, theology, feminist theology, prophetic call and mission,” she stressed. The young nuns should be taught relevant church documents, emerging trends in spirituality and religious life, and feminist interpretation of the Bible, she added.

She agrees the task ahead is immense. “We need to conscientize our sisters and our hierarchy and be firm that we shall decide our own future and our involvement in the Indian church by and for ourselves. We are adult enough to manage ourselves,” she said.

D’Lima wants the nuns to choose service instead of servitude. “The important thing is to dialogue with those who tend to impose on us, making known our stand with confidence and conviction leading to collaboration, rather than an either-or situation.”

She cited her own experience when she was superior general of the Society of the Daughters of the Heart of Mary. An apostolic visitor was sent to them “for reasons which I did not know. He was supposed to examine the governance of my congregation and I had to defer everything to him. But I did not.”

She was summoned to the dicastery in Rome several times to undergo questioning about her governance. “I did not engage any lawyer but honestly answered whatever I was asked to clarify. I suffered a lot through it, but in the end I not only completed my term as superior general but was elected for a second term.”

She said the experience convinced her that one does not have to say yes to everything.

“I was able to take the fight to the Vatican, and I believe God’s grace was there to help me. Your conviction in what you are doing and your faith in God will give you the courage to act and be independent. The Spirit is one of us. She inspires women as well.”

Pinto encouraged the forum: “The women religious of our time cannot allow a church in dire need of reform to continue in its broken state. They have to speak up.”

This story appears in the Abuse of sisters feature series. View the full series.